by Steve Knapp & Rob Taylor

If you’re looking for something to help inspire your sales personnel (at any level) help them to improve their sales strategies and add more value to your organization then this is the book for you. Steve and Rob do an excellent job of disseminating some key selling strategies through a storytelling aspect.

With two very strong forewords by Tina Reading (Editor of Lube Magazine) & David Wright (Director General, United Kingdom Lubricant Association), the book gets off to an incredible start. Tina talks about the way this book leads the way in showing the reader how to navigate change. David advocates that this book is a blueprint for the entire commercial lubricants ecosystem to allow them to evolve with confidence.

This book follows the journey of a salesman, Dan who was at the top of his career making the usual moves to push lubricants and succeeding in the past. However, especially after COVID-19, the sales strategies changed and even after the lockdowns, they didn’t revert to the old ways. Many sales personnel actually lived through these emotions and the way Steve & Rob describe the scenarios makes it very easily relatable.

What sets this book apart is that the change in selling strategy was just the beginning of the book. These gents, expertly showcase ways that worked and didn’t work for the hero of the story, Dan. They introduce selling techniques which hinge on adding value to the organization and inform the salespeople that there is a buyer revolution happening. They describe the buyer revolution to salespeople to help them understand the change in the market and how they can prepare to better serve their customers.

On Dan’s journey, he is met with roadblocks (like CRM!) which he did not like before but after exploring and understanding it better, is now one of his tools in his Sales kit. The gents also speak about Dan’s journey (and hesitancy) with using the social platform LinkedIn and the LinkedIn Sales Navigator.

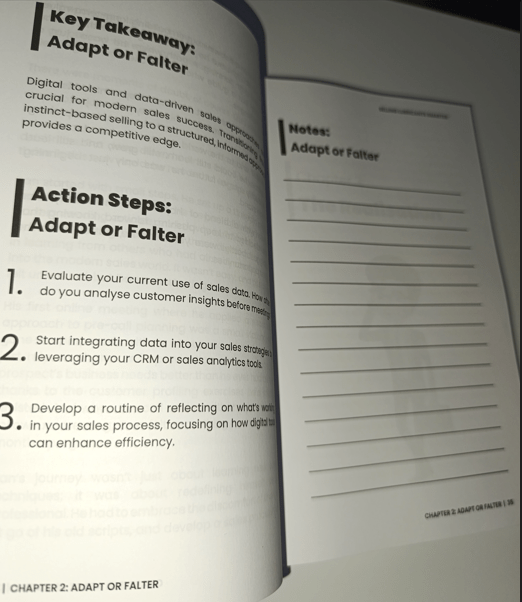

This book is filled with so many golden nuggets to help both salespeople and managers to better understand the buyer’s revolution. These strategies aren’t just based on hearsay, they are grounded in more than 25,000 Buyer Revolution data points. At the end of each chapter, there are key takeaways, action steps and a place for notes! This turned the book into an even more value-added resource for salespeople!

I highly recommend this book for anyone in the lubricants industry as we have all been a “Dan” in one way or another.

Check out the Kindle version here.

Be sure to follow Steve Knapp & Rob Taylor on LinkedIn.

Check out the book's website here: https://sellinglubricantssmarter.com/

or Steve & Rob's Website here: https://plangrowdo.com/