To ensure these oils remain healthy (and not contaminated or degraded), a few basic tests can be performed on all compressors, regardless of type (reciprocating, screw, refrigerant, etc.). These include:

- Viscosity – this is key as some of the gases can easily affect the viscosity, which (if decreased) will not provide adequate separation for the interacting surfaces and cause wear. Generally, a ±10% limit is used (though OEMs may use different values).

- Acid Number – if this begins increasing, then we have an accumulation of acids in the oil, which can be because of contamination. For most compressors, a 0.2 mg KOH/g increase is the warning limit, but for refrigeration compressors, the limit is tighter at +0.1 mg KOH/g. Always check with your OEM for these limits.

- Water content – changes by OEM and refrigerant type, as the different gases will have varied tolerances.

- Wear metals – these values will vary as per OEM, as well, since they are all designed with different types of metals. Users should look for trends or significant increases in these values to indicate wear.

Some specialty tests for compressors include:

- MPC (Membrane Patch Colorimetry) – this helps to measure if there is any potential for the oil to form varnish. Given the high temperatures these types of equipment endure and the potential for contamination, the oil is at risk of forming varnish. While limits will vary by OEM, some general guidelines to follow are 0-20 Normal, 20-30 Warning, >30 Action required

- RULER® (Remaining Useful Life Evaluation Routine) – this quantifies the remaining level of antioxidants in the oil. When oxidation occurs, the antioxidants get depleted. As such, by monitoring antioxidant levels, one can easily determine whether oxidation is happening in the oil. The general rule of thumb is that if the level falls below 25%, there are not enough antioxidants to keep the oil healthy and prevent degradation.

- Air Release (DIN ISO 9120) – measures the ability of the oil to allow air to escape and not keep the air in the oil. If air bubbles remain in the oil, this can be devastating, as it can lead to micropitting, cavitation, or increased oxidation. Users can trend the values; if they increase, it indicates that the air is taking longer to be released, which means it is staying in the oil and in the system longer.

- Particle Count – this can identify if there are any contaminants in the system. These oils must be kept clean, and OEMs typically specify target cleanliness levels.

Compressors are critical equipment, and we must understand how they work and the lubricant specifications required. Monitoring their health can also help us avoid unnecessary downtime and keep our facilities running.

References

- Mang, T., & Dresel, W. (2007). Lubricants and Lubrication. Weinheim: WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA.

- Totten, G. E. (2006). Handbook of Lubrication and Tribology – Volume 1 Application and Maintenance – Second Edition. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

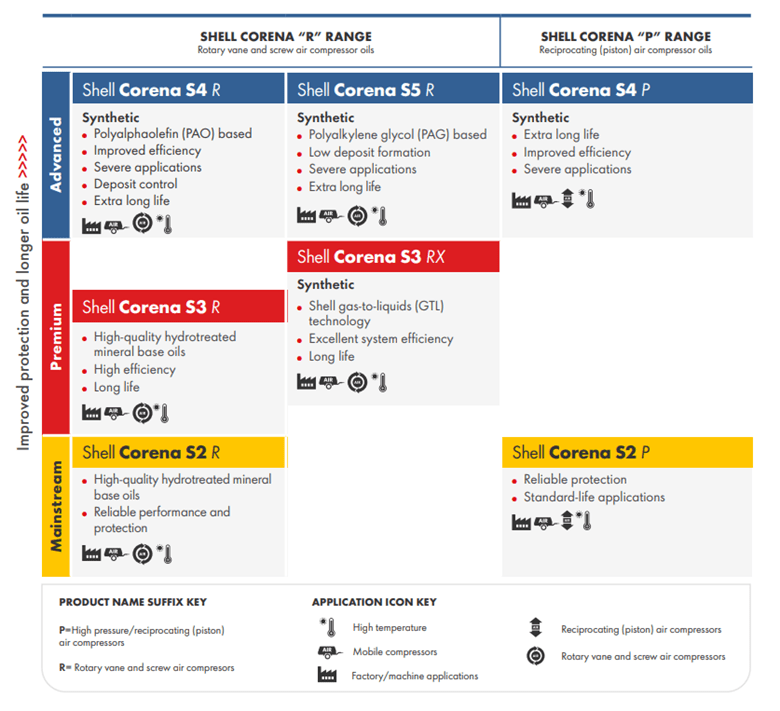

- Shell Lubricants. (2025, November 08). The Shell Corena range. Retrieved from Shell Lubricants Compressor Oils: https://www.shell.com/business-customers/lubricants-for-business/products/shell-corena-compressor-oils/_jcr_content/root/main/containersection-0/simple_1354779491/promo_1484925192/links/item0.stream/1759302155345/17be2a9a74057f321bb209128933f68f8b88ca70/s

- ExxonMobil. (2025, November 08). Refrigeration Lubricant Selection for Industrial Systems. Retrieved from ExxonMobil Lubricants: https://www.mobil.com/lubricants/-/media/project/wep/mobil/mobil-row-us-1/new-pdf/refrigeration-lubricant-selection-for-industrial-systems.pdf

- Chevron Lubricants. (2025, November 08). Optimizing compressor performance and equipment life through best lubrication practices Chevron. Retrieved from Chevron Lubricants: https://www.chevronlubricants.com/content/dam/external/industrial/en_us/sales-material/all-other/Whitepaper_CompressorOils.pdf

Find out more in the full article, "Compressor Oil, Types, Applications and Performance Drivers" featured in Precision Lubrication Magazine by Sanya Mathura, CEO & Founder of Strategic Reliability Solutions Ltd.