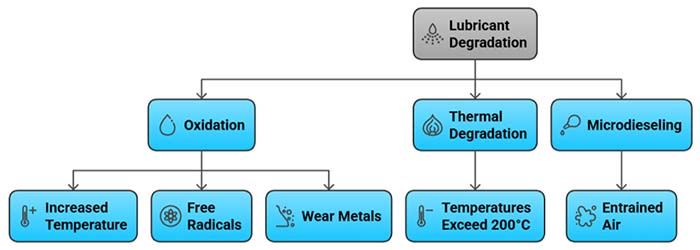

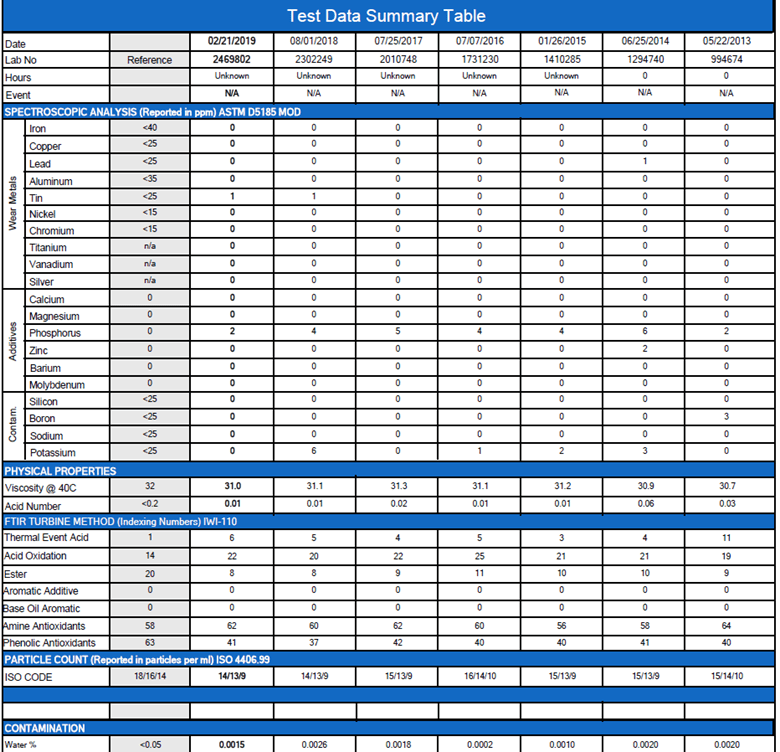

Choosing the right oil for the system is just one part of the puzzle. How do we know the oil is performing when it’s in the system? This is where condition monitoring can work hand in hand to help ensure that the oil does not fail the asset.

If a proper oil analysis program does not exist, operators will not know whether the oil is properly lubricating the asset. They will also not be aware of whether the oil is breaking down too quickly and failing to protect the asset. Oil analysis can also alert operators to signs of wear in the asset, so they can fix them before they turn into functional failures.

An oil analysis program that lives in a drawer protects assets about as well as no program at all.

There is also the possibility that an oil analysis program exists but is not top of mind, or that its results are put in a drawer. This can also cause the asset to fail even though the correct oil is being used. Apart from the aforementioned factors, if operators are not warned of the impending failure of the oil, this can result in production losses, increased downtime, and, in some extreme cases, the complete loss of the asset if it has failed beyond repair.

Incorrect sampling is another area in which the actual condition of the asset is not reported. Even with the correct oil used, if a sample is collected from a dead leg or an area that is not truly representative of the conditions inside the component, its actual condition will not be known. With incorrect data about the component, the asset can be misdiagnosed or treated for symptoms that do not exist, which can lead to its detriment.

Human and Organizational Factors

Not all failures occur at the equipment level; human and organizational factors can also cause the asset to fail even when the correct oil is used. If humans aren’t properly trained in oil sampling techniques or storage and handling practices, these can affect the asset’s functionality. We often forget that, at the heart of it all, lies the human factor, which is partially governed by the organization’s systems.

Training needs are an organizational factor that is often overlooked when considering how an asset can fail. However, if operators have not been trained in condition monitoring techniques, they will not be able to read oil analysis reports or take appropriate actions to protect the asset. Training can help bridge some competency gaps that directly impact asset performance.

It doesn’t matter what oil is in the system if no one is trained to monitor it – or motivated to care.

Culture is another factor swept under the rug. If the culture doesn’t exist to look after the assets, it doesn’t matter what type of oil is placed in the system; the asset will fail eventually. The performance of the asset does not only rely on using the correct oil. By implementing a culture of Asset ownership, where operators look after the asset and are accountable for its performance, assets are optimized to provide the functionality they should. This is one way to ensure the right oil is used to enable the assets’ performance.

Another area of concern is the documentation of maintenance procedures. If maintenance procedures are not adequately documented, someone new to the operation may not be aware of the correct practice. This, coupled with a lack of training, can spell disaster for the equipment. In these cases, even though the right oil was selected, the wrong practice or lack thereof can fail the asset.

Turning the “Right oil” into the “Right Outcome.”

As explained in this article, improper practices can jeopardize the asset’s health, even when the right oil is used. However, if all the right things align, we can have an asset that lasts for its expected lifetime or beyond.

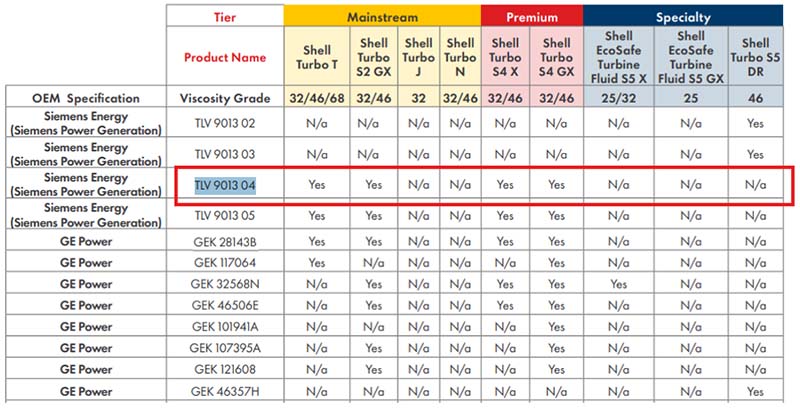

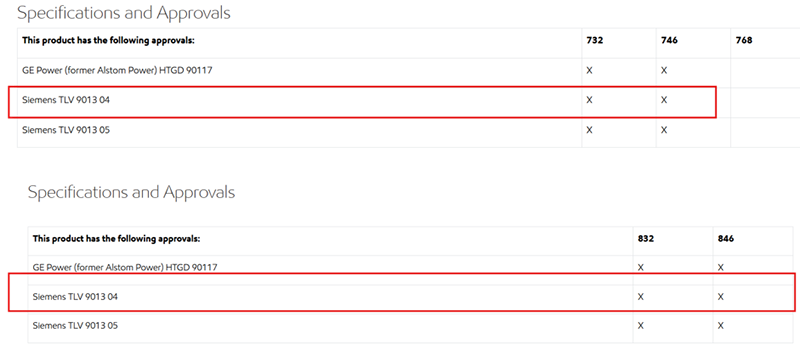

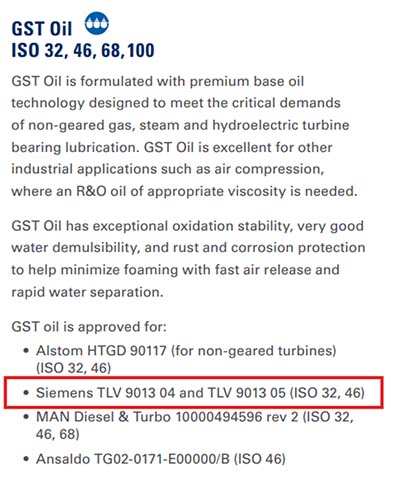

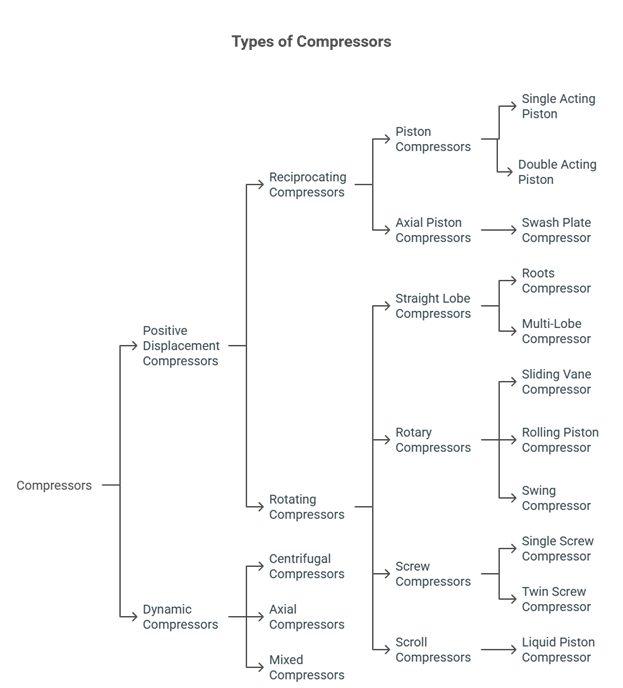

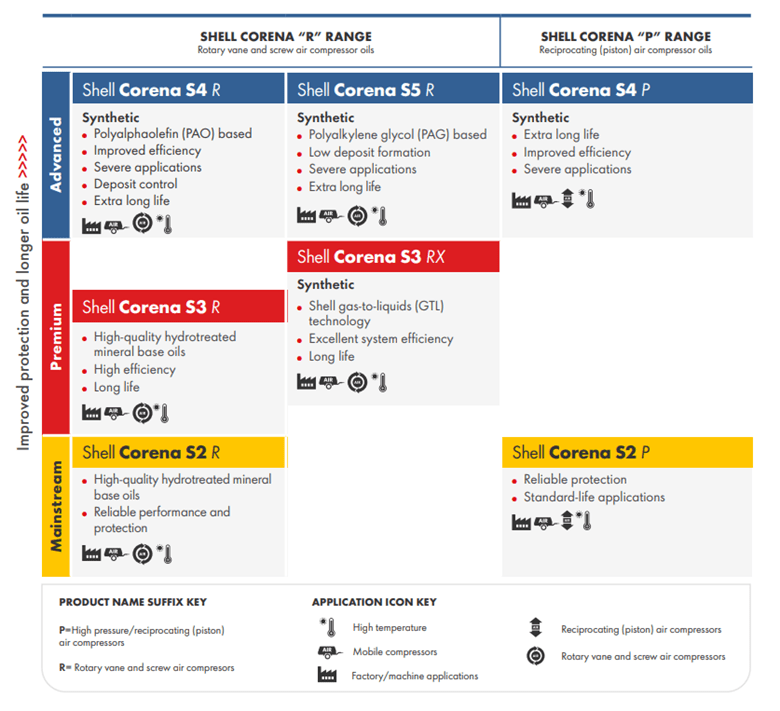

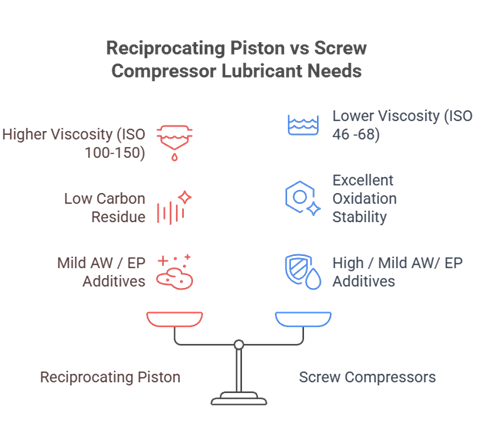

This starts with selecting the right oil based on the application, environmental conditions, and OEM recommendations. If we follow this up with good storage and handling practices, proper condition-monitoring programs, documentation, and training, we can look toward a longer-lasting asset. The right oil enables reliability – but only disciplined practices deliver it.

Find out more in the full article, "When 'Right oil, Wrong practice' still fails assets" featured in Precision Lubrication Magazine by Sanya Mathura, CEO & Founder of Strategic Reliability Solutions Ltd.