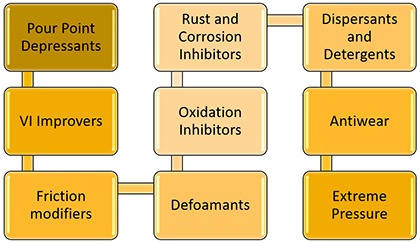

Different additives have successfully suppressed the degradation of finished lubricants6, 10. These include:

- Radical scavengers/inhibitors, also called propagation inhibitors

- Hydroperoxide decomposers

- Metal deactivators

- Synergistic mixtures

Each of the above listed performs in a particular way to reduce the oxidation process in the lubricant.

Radical Scavengers

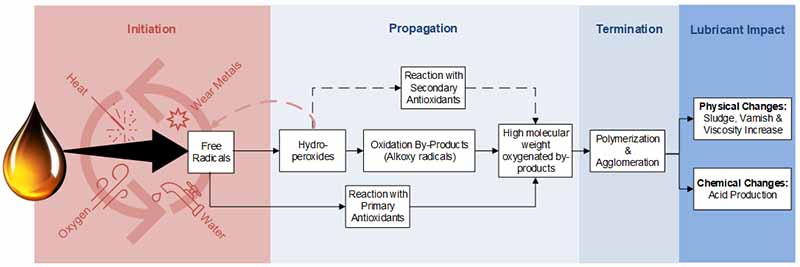

Many applications use radical scavengers as their preferred antioxidant. Radical scavengers are also known as primary antioxidants, as they are the first line of defense in the oxidation process. These are phenolic and aminic antioxidants.

They neutralize the peroxy radicals used during the initiation reaction to generate hydroperoxides4. These neutralized radicals form resonance-stabilized radicals, which are very unreactive and stop the propagation process.

Some examples of these additives are1: diarylamines, dihydroquinolines, and hindered phenols. While they may be known as simple hydrocarbons, they are often characterized by low volatility, used in quantities of 0.5-1% by weight, and have long lifetimes10.

These primary antioxidants are usually very effective at temperatures below 200°F (93°C)7. At these temperatures, oxidation occurs at a slower rate. These primary antioxidants are typically found in applications involving turbines, circulation, and hydraulic oils intended for extended service at these moderate temperatures.

Hydroperoxide Decomposers

The role of hydroperoxide decomposers is to neutralize the hydroperoxides used to accelerate oxidation. Radical scavengers (primary antioxidants) neutralize the free radicals, and these hydroperoxides are formed after the initiation stage. As such, hydroperoxide decomposers are known as secondary antioxidants.

These decomposers convert the hydroperoxides into non-radical products, which prevent the chain propagation reaction. ZDDP is one example of this type of decomposer, although organosulphur and organophosphorus additives have been used traditionally.

Metal Deactivators

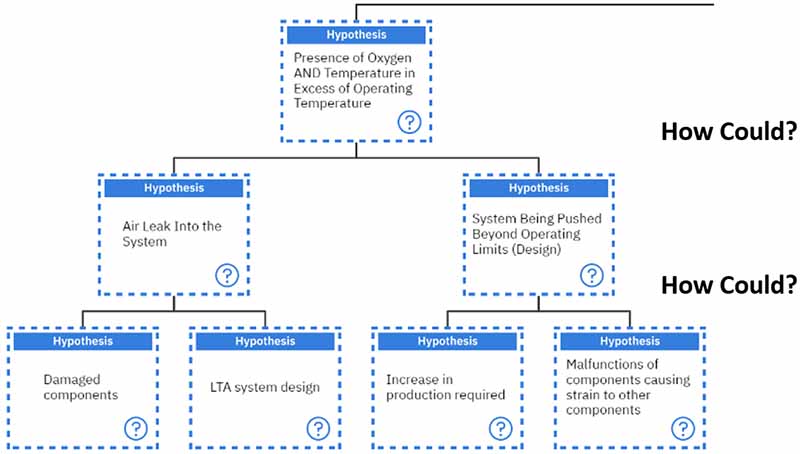

Metal deactivators are usually derived from salicylic acid10. These function by entraining a metal such as copper or iron to inhibit oxidation acceleration. However, when the operating temperatures exceed 200°F (93°C), this is the stage at which the catalytic effects of metals begin to play a more important role in accelerating oxidation7.

Therefore, during these conditions, an antioxidant that can reduce the catalytic effect of the metals should be used, such as metal deactivators. These react with the surfaces of metals to form protective coatings. One such example is zinc dithiophosphate (ZnDTP), which can also act as a hydroperoxide decomposer at temperatures above 200°F (93°C).

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid is another commonly used example of this type of antioxidant.

Synergistic Mixtures

As explained above, there are different types of antioxidants, but one thing remains the same: They can work better when they work together. Some antioxidants can work in a synergistic manner to provide added protection to a finished lubricant. There are two types of synergism: homosynergism and heterosynergism.

Homosynergism occurs when two different types of antioxidants can be classed under the same category. One example is the use of two different peroxy radical scavengers. These both operate by the same stabilization mechanism but differ slightly in formulation.

On the other hand, heterosynergism is more common and often seen with aminic and phenolic antioxidants. Aminic antioxidants are primary antioxidants and radical scavengers, while phenolic antioxidants are secondary antioxidants and hydroperoxide decomposers.

In this case, the amnic antioxidants react faster than phenolic antioxidants, and as such, they are used up when the lubricant undergoes oxidation. However, the phenolic antioxidant regenerates a more effective aminic antioxidant, which helps suppress the rate of oxidation.

Find out more in the full article, "Antioxidants in Lubricants: Essential or Excessive?" featured in Precision Lubrication Magazine by Sanya Mathura, CEO & Founder of Strategic Reliability Solutions Ltd.