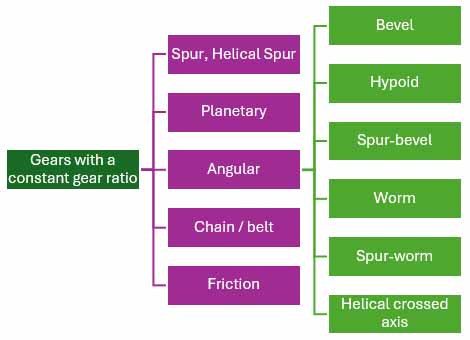

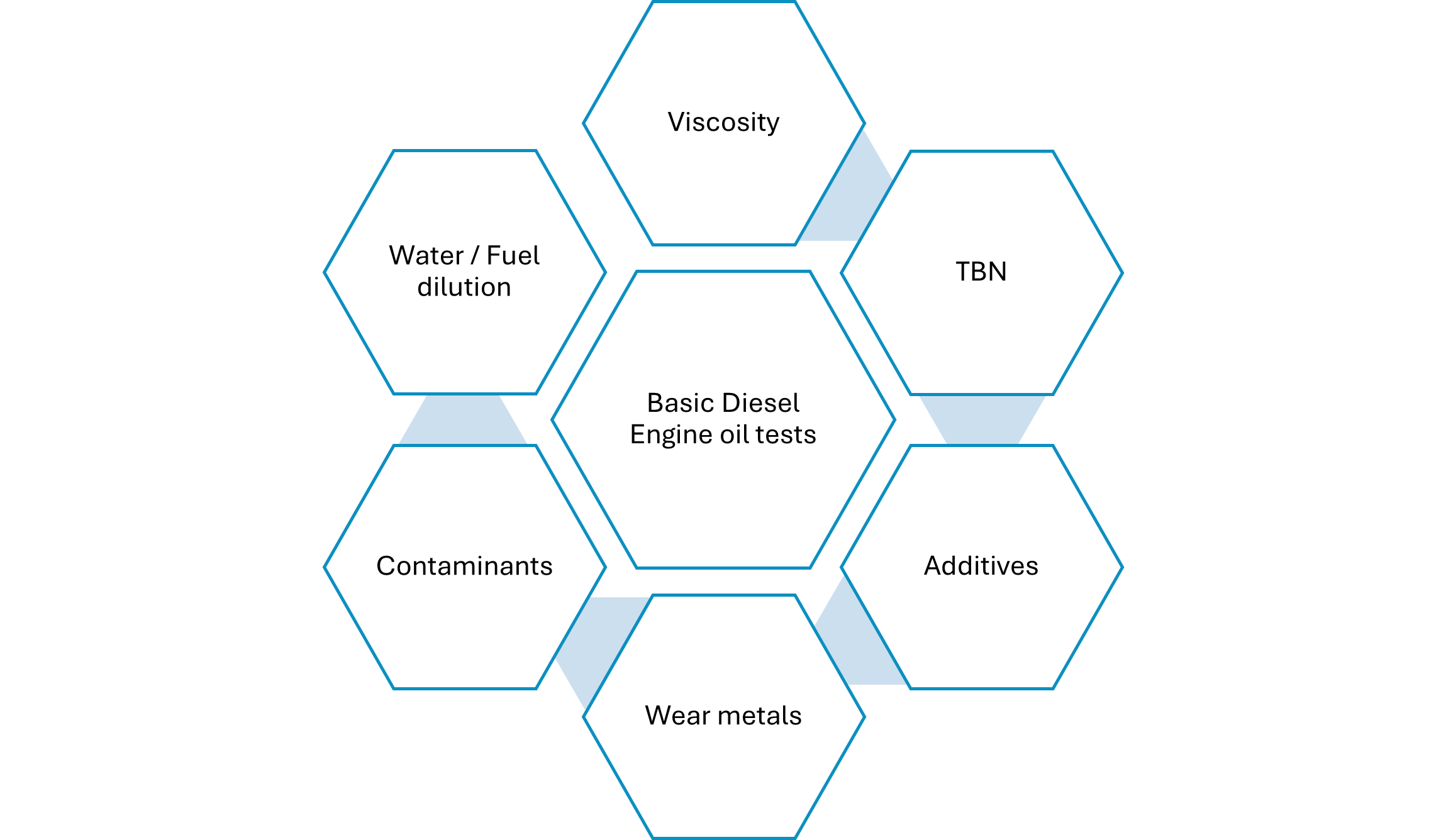

Viscosity (American Society for Testing and Materials D445) – The viscosity levels should ideally fall within ±5% of the original value. If they exceed ±10% of the original value, then the levels will fall out of the classification for that grade of oil.

For instance, Mobil Delvac 15w40’s kinematic viscosity, at 100°C, is 15.6 millimeters squared per second (mm2/s), according to its technical data sheet. If this value drops below 14.04 mm2/s or above 17.16 mm2/s then it can no longer be classed as a 15w40 oil and will not be able to properly lubricate the engine. These values vary depending on the manufacturer, application of the oil and the lab being used. These are a guideline in this example.

TBN– This is the amount of alkalinity remaining in the oil. The oil’s alkalinity helps neutralize the acids formed in a diesel engine. This value is always depleting as acids are continuously forming in an engine. However, if the TBN value drops below 40% to 50%, then there isn’t much reserve left to continue to protect the oil. This is the threshold limit, which can vary depending on the application, but this is a good guide to follow.

Additives – All finished lubricants have additive packages. These will vary depending on the oil producer. However, a few additives should be on your radar when trending their depletion in diesel engine oils. These include zinc, phosphorus, magnesium and calcium. These additives typically form parts of the dispersant, corrosion and antiwear additives that protect the oil. Ideally trending the decline of these may be helpful but your lab would have reference values (based on the type of oil) and can advise on concerning levels.

Wear metals – During the engine's lifetime, components will wear. Depending on the engine’s manufacturer, the warning limits will also vary (this also differs depending on the application). Iron, aluminum, chromium, copper, lead, molybdenum and tin are some metals to trend. If other special metals are in your engine, then you can ask your lab to include them in the oil analysis report. Typically, if there is an upward trend, this indicates wear/damage of specific components.

Operators can perform a simple test to determine if metal filings are in their oil (indicating some form of wear). They can place the oil in a shallow container and then place a magnet below the container or place the magnet in a sealed plastic bag and immerse it into the container. When the magnet is removed, if there are metal filings on the magnet, then this indicates the presence of wear metals, and the mechanic should begin investigating for damaged components.

Contaminants– These include any material which is foreign to the lubricant. Typically, labs test for the presence of sodium and silicon. Depending on the application’s environment, these values can increase indicating that they are entering the system somehow. Usually, this can occur during lubricant top-ups or improper storage and handling practices.

Presence of water – This is never a good sign because water can affect the lubricant by changing its overall viscosity, bleaching out some of the additives and even acting as a catalyst. Many labs perform a crackle test (where the oil is heated and if it produces a “pop” sound, then that confirms water in the lubricant. In certain instances, it is obvious that there is water present because it settles out in the sump/container. Labs can also perform a test to quantify the volume of water present. Typically, 2,000 ppm to 5,000 ppm is too much for most applications but this varies depending on the manufacturer.

Operators can perform their version of the crackle test by placing some of the oil in a metal spoon and heating it with a flame. If it produces a pop, then they can confirm that the oil has too much water in it before sending it off to the lab. Note: This should not be done in a highly flammable environment!

Fuel dilution – This occurs in most diesel engines due to the nature of the engine. However, limits need to be adhered to because too much fuel in the oil can lead to drastic changes in its viscosity. Usually, this value should not exceed 6%, but this can vary depending on the application and the manufacturer.

One way that operators can find out if there is fuel in their oil is to place a small drop of the oil on a coffee filter and leave it to “dry” for some time. The oil will spread out in concentric rings and if there is fuel present, there will be a rainbow ring. This means that the mechanics need to figure out if there is an issue with any of the injectors or seals in the diesel engine.

Ideally, the main idea with oil analysis is to develop a trend for your equipment and understand how the values align over time. This can help operators spot if an inaccurate sample was taken (possibly after a top-up, directly after an oil change or even from the bottom of the sump). An analysis also assists in planning the maintenance of components. For instance, if the value of iron in the oil analysis report keeps increasing then there is a strong possibility that some iron component is wearing. This can give the mechanic the time they need to investigate the engine and replace the component before it causes unscheduled downtime.

Protect One of Your Greatest Assets

Your diesel engine oil is one of the greatest assets in your fleet. You should be able to use an oil that aligns with your application while slowing its degradation rate with good practices and managing its health. Diesel engine oils form a critical part of your operation and deserve attention.

References

American Petroleum Institute. (November 18, 2016). New API Certified CK-4 and FA-4 Diesel Engine Oils are Available Beginning December 1. Retrieved from API: https://www.api.org/news-policy-and-issues/news/2016/11/18/new-api-certified-diesel-engine-oils-are

American Petroleum Institute. (February 19, 2024). API's Motor Oil Guide. Retrieved from API: https://www.api.org/-/media/files/certification/engine-oil-diesel/publications/motor%20oil%20guide%201020.pdf

The International Council on Combustion Engines. (2004). Guidelines for diesel engines lubrication - Oil Degradation | Number 22. CIMAC.