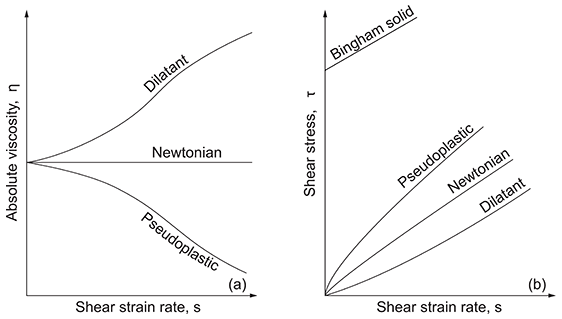

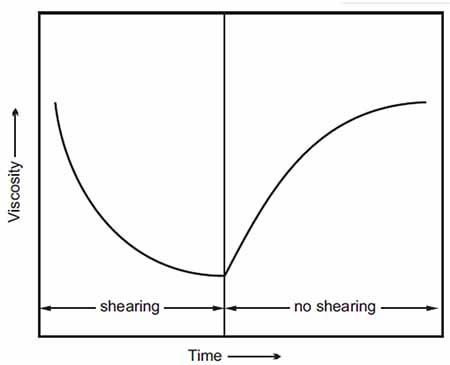

The viscosity of oil is one of its most essential characteristics. Thus, it is important to understand how this is measured and quantified. There are two main types of viscosity, dynamic (or absolute) and kinematic viscosity.

The dynamic viscosity measures the force required to overcome fluid friction in a film and is reported in centipoise (cP) or in SI units Pascal Seconds (Pa s) where 1 Pa s = 10 P (Poise). It can also be considered the internal friction of a fluid. This is usually used for calculating elastohydrodynamic lubrication related to rolling element bearings and gears.

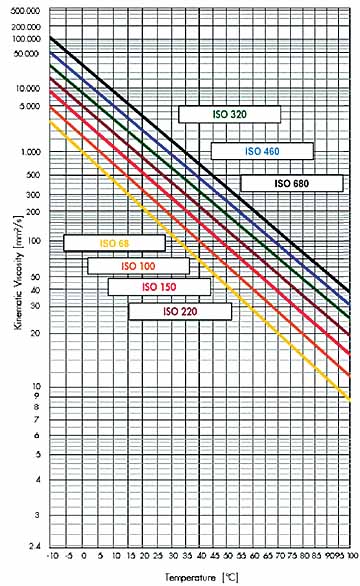

On the other hand, the kinematic viscosity of a fluid is the relative flow of a fluid under the influence of gravity. Its unit of measure is centistokes (cSt) which in SI units is mm2/s, 1cSt = 1 mm2/s. (Mang & Dresel, 2007).

Kinematic Viscosity = Dynamic Viscosity / Density

Other units of measure for viscosity include; Saybolt, Redwood, and Engler, but these are less widely used than the cSt or cP, especially for lubricants.

Oil Viscosity Grades and Standards

One of the best-kept secrets about viscosity is that a particular grade often represents a range. When oils are classified, one may see an ISO 32 or ISO 220 and believe that the oil will have this exact viscosity (32 cSt or 220 cSt). However, this is not the case.

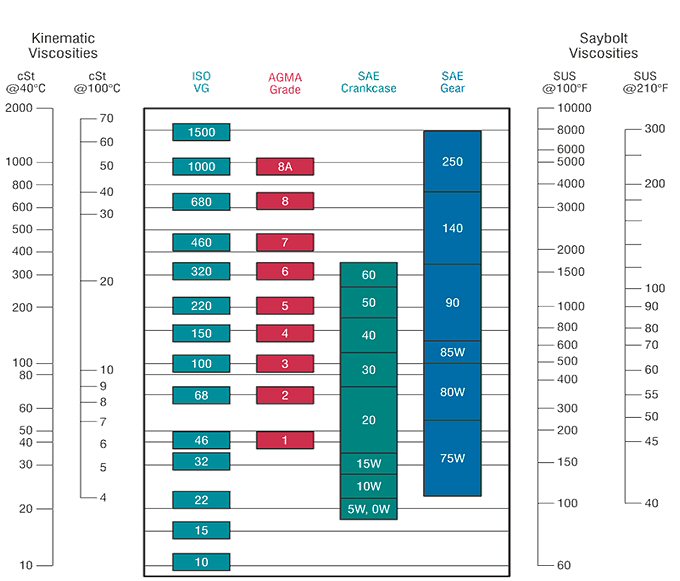

There are three general classifications where viscosity grades have particular ranges based on the fluid type. The fluid may behave differently in each application, hence the need for these three scales. However, there is a chart that allows users to convert the various scales into the one needed.

Engine Oil Classification (SAE J300)

As per the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE), the SAE J300 standard classifies oils for use in automotive engines by viscosities determined at low shear rates and high temperature (100°C), high shear rate and high temperature (150°C) and both low and high shear rates at low temperature (-5°C to -40°C) (Pirro, Webster, & Daschner, 2016).

Engine manufacturers have widely used this system to aid in designing lubricants suited for these applications. As such, oil formulators also adhere to these classifications when engineering lubricants.

One will note the use of the suffix letter “W” in some of the grades below. These oils are intended for low ambient conditions, whereas those without the “W” are intended for oils that will not encounter low ambient conditions.

These are commonly described as multigrade (where the “W” is found between two numbers) and monograde oils (where the “W” is at the end or the grade is identified by a number only) in the table below.

The table shows that the viscosities must fall within a particular range to be classified. For instance, a 5W30 oil should meet the specifications of:

- Low temperature, Cranking viscosity of 6600 cP at -30°C

- Low temperature, Pumping Viscosity Max with No Yield Stress of 60,000 cP at -35°C

- Low shear rate Kinematic viscosity at 100°C should be between 9.3 -12.5 cSt

- High Shear rate viscosity at 150°C Max at 2.9 cP

One will notice the range of 9.3 to 12.5 cSt (at 100°C). This is where oils can be blended to either end of this scale but still achieve the classification of a 5w30 oil.

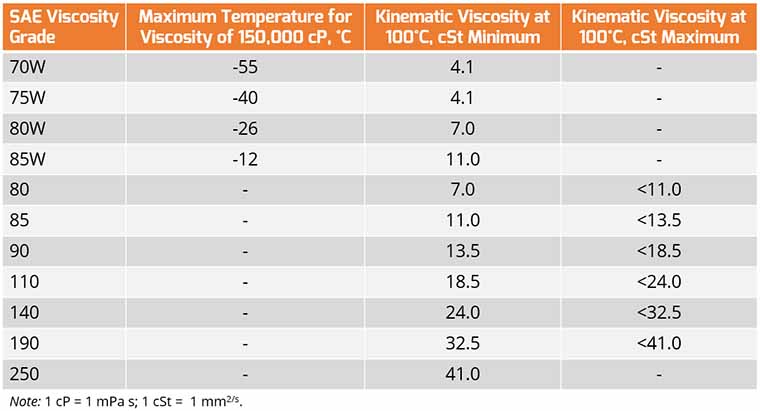

Axle and Manual Transmission Lubricant Viscosity Classification (SAE J306)

As per the SAE recommended practice J306, automotive manual transmissions and drive axles are classified by viscosity, measured at 100°C (212°F), and by the maximum temperature at which they reach the viscosity of 150,000 cP (150 Pa s) when cooled and measured in accordance to ASTM D2983 (Method of Test for Apparent Viscosity at Low Temperature Using Brookfield Viscometer). (Pirro, Webster, & Daschner, 2016).

The table below shows that for an SAE grade of 190, the kinematic viscosity must fall within the range of 13.5 to 18.5 cSt at 100°C. While most viscosities tend to fall mid-range of these values, it also indicates that if the lubricant achieves 18 cSt at 100°C, it can still be classified at an SAE grade 90.

The most common multigrade lubricants within this grade fall within the 80w90 or 75w140 classifications.

Another factor for these types of lubricants is API GL4 or GL5 ratings. It must be noted that a GL5 lubricant is recommended for hypoid gears operating under high-speed, high-load conditions.

On the other hand, a GL4 lubricant is usually recommended for the helical and spur gears in manual transmissions and transaxles operating under moderate speeds or loads. These should not be used interchangeably as the GL5 lubricants tend to adhere to the surfaces and may cause more damage in a GL4 application.

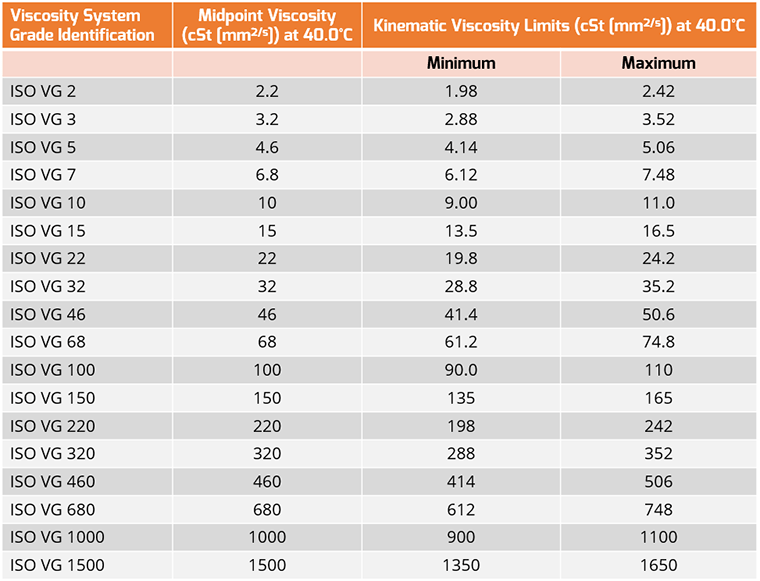

Viscosity System for Industrial Fluid Lubricants

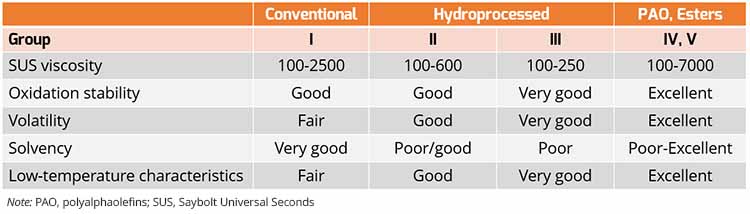

This classification was jointly developed by the ASTM and STLE (Society for Tribologists and Lubrication Engineers). Initially, the system was based on viscosities measured at 100°F but converted to viscosities measured at 40°C.

ASTM D2422 and ISO 3448 are the references for this system. In this system, it is clearer to see the variances in the ranges of viscosities. In this case, the mid-point of the range is used as the ISO viscosity. To determine the range of any ISO viscosity, one can calculate ±10% of the mid-point value to get the minimum and maximum values of the range.

All of these systems can be represented in the figure below, where it is easy to calculate the oil viscosity using another system:

Find out more in the full article, "Oil Viscosity - A Practical Guide" featured in Precision Lubrication Magazine by Sanya Mathura, CEO & Founder of Strategic Reliability Solutions Ltd.